Kennick Burn & Laurieston Forest

Heavy snowfall at Kennick Burn

KENNICK BURN | LAURIESTON FOREST | DUMFRIES & GALLOWAY | DG7 2PT | GRID REF NX630621

Kennick Burn runs through Laurieston Forest, most easily accessed on the moor road to Gatehouse of Fleet where there is a short circular walk along the burn and waterfalls where you may see red squirrels, otters and red kites.

The mix of habitats in and around Laurieston already offers a good starting point for general biodiversity and the timber crop forestry plantations which have historically cut into large expanses of open moor now offer potential for conservation of threatened species such as nightjars and black grouse. [1] Annex 1, EU Birds Directive

Heather scrub, purple in late summer makes a bright carpet between young saplings; jays swoop between pockets of mixed native trees; magnificent beech trees make emerald tunnels above the road and lochs and rivers make a network of wet areas across the habitat.

The forestry area is part of the Galloway Forest Park and is managed by Forestry and Land Scotland. Though the area is largely utilised for commercial forestry, it is a significant national breeding site for the migratory European Nightjar BAP (Caprimulgus europaeus) and consequently there are management plans developed in consultation with the RSPB to ‘maintain and enhance’ the habitat network.

‘92% of Scotland’s population of nightjars (RSPB, 2005) live in a handful of sites in Dumfries and Galloway. Laurieston forest block is one of these key sites and management will continue in consultation with RSPB over areas which are believed to be key to the nightjar. The combination of introducing a strip shelterwood system to the east of the forest, maintenance of the existing group shelterwood system and the use of smaller clearfell coupe size should all combine to enhance habitat availability for this species. The shelter wood systems are shown in concept map (map 5) and LISS map (map 1)’

– [2] Forestry and Land Scotland, Laurieston Land Management Plan 2018-2028

Nightjars are unusual to see, particularly as far north as Scotland; not only are they uncommon in the first place, but also they are nocturnal and crepuscular (more active at dawn and dusk), roosting or sitting on eggs during the day where they are well camouflaged by earth coloured markings and mottled feathers. They are summer residents, overwintering in Africa, reducing chances of seeing them to the summer months between April/May to August. Perhaps because of this their behaviour and requirements are not currently well understood and they are still being studied. Despite their elusiveness, the males can be distinguished by their ‘churring’ cricket-like territorial call and wing clapping displays and are surveyed in this way by counting the number of churring males heard [3] after sunset or before dawn.

Nightjars have suffered substantial declines in the UK through habitat loss, coinciding with the continued establishment of mass conifer plantations on moorland and heathland landscapes. In the 20 years preceding 1992, the UK breeding range more than halved, with over half of the entire UK population in ten or fewer sites [4] (Gregory et al. 2002) as a result they were Red listed and targeted as a Priority Species on the UK Biodiversity Action Plan and subsequent UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework. [5] (JNCC)

In 1992 the second national survey detected an increase in population of more than 50% since 1981 [6] (Morris et al. 1994), which coincided with the maturation and clear-felling of conifer plantations across the UK and a new dependence on these cleared or re-stocked areas was identified. However, concern that the usefulness of these ‘new habitats’ would only last for a number of years before tree growth would make them un-beneficial again meant looking at a change in forestry management. Despite a generalised population recovery, the increase in range expansion remained minor, in addition the 2004 survey estimated almost complete area loss both across Scotland and in south west Scotland, with the only stronghold remaining in Dumfries and Galloway [7] (Conway, G. & Henderson, I., 2005).

Between 1992-2004 various BAP targets were met, with an estimated UK population increase of 36% and an increase in occupation of heathland habitats following restoration and (re)creation projects. In Scotland, however, there was evidence of population decline and range contractions with UKBAP targets to restore Nightjars to areas of former range not met and all remaining males now associated with forestry plantations with none remaining on heathland. [8] (Conway et al. 2007). In Dumfries and Galloway, FES (now Forestry and Land Scotland) has worked with groups such as RSPB and the local Nightjar Study Group to encourage targeted conservation. In 2016, 40 churring males were recorded in Dumfries & Galloway, [9](RSPB & FES 2016) twice as many as the previous year and the highest numbers since surveying started in 1981 [10] (RSPB 2017).

From what has been learnt in recent decades, nightjars benefit from a mosaic of different habitats, preferring heathland, moorland and peatland; open glades within or next to forests; as well as clearings of freshly felled or newly planted conifers which are mainly used for breeding and nesting. In addition to this, they utilise deciduous or mixed woodland areas for foraging, feeding on moths and beetles, in preference to conifer plantations, arable fields or improved grassland, even if this means travelling considerable distance each night to do so [11] (Alexander & Cresswell 1990). Despite higher abundance of prey in mature forest, nightjars can prefer to forage in areas with younger growth, possibly because of ease of capture [12] (K. Sharps et al.). It is seemingly these fringes of soft vegetation and young growth between natural habitats and forestry plantations which could now provide a managed beneficial habitat for them, and offer a solution to the hard-edged more mature commercial forestry which is inhospitable for most biodiversity.

It is perhaps interesting and useful to look for clues about their naturally preferred habitats in older writings from last century; in a book compiled between 1885-1897 issued by Lord Lilford, who was president of the British Ornithologists’ Union, the alternative name of fern-owl is given for the nightjar, with the following description:

‘The favourite haunts of our bird are shady woods, commons overgrown with fern and heather, and it is occasionally to be found also on rocky hill-sides amongst brambles; but I have never found it established at any considerable distance from more or less extensive patches of the common fern or bracken.’

– [13] Excerpt from Coloured figures of the birds of the British Islands, issued by Lord Lilford, F.Z.S,

president of the British Ornithologists’ Union. Vol 2. 1885-1897.

"n69_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

"n69_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus) plate from Coloured figures of the birds of the British Islands / issued by Lord Lilford.. London :R. H. Porter,1885-1897.. litho W. Greve, Berlin.

Reading this, points to the possibility that it could be more about the type of fern availability than the specific forest fringe location itself. It is common for newly disturbed areas such as cleared commercial forest, to be quickly colonised with bracken. However, bracken is well established across the UK, engulfing huge swathes of land, in no short supply if that is the specific requirement for nightjars. It poses the question of whether the author’s bracken is the same highly competitive species as the Pteridium aquilinum we refer to now.

Some research into the history of bracken [14] (Page, 1982) & [15] (Stewart, 2005) suggests that although it would have been the same species, the habit and range of bracken has changed considerably in the last century. Where bracken would have been growing in forest clearings, the growth would have been naturally checked by other competitors and shady borders; hence the growth would have been thinner and weaker, a more minor component of the ground flora. The de-forestation, ground disturbance, burning and over-grazing practices of past years have encouraged bracken to spread more and spore more into open land and grow more vigorously in the acid soils which would have been predominantly heather based, creating dense stands of vegetation which obliterate much other biodiversity. Similarly to monoculture in forests, the same plant which would have offered protection and shelter for other forest plants and insects, now makes a habitat inhospitable for most species. It may then be that the areas of newly felled conifers are partially beneficial to the nightjar because they offer new and less-established areas of bracken which are not too dense to begin with. Perhaps, then the solution to both conserving nightjars and controlling the spread of invasive bracken thickets (and related tick issues) is to reintroduce other species of grass and woodland plants and replant less dense, mixed forest cover with clearings, effectively restoring the habitats which we have altered.

Laurieston forest is an interesting example of how habitats can be managed to benefit certain species and encourage biodiversity. Natural landscapes that have been altered simply cannot be restored; whilst we continue to destroy remaining reserves, species will suffer loss or extinction. However, there is hope for compromise between human land use and nature where it has already been damaged. More and more, it is becoming obvious that the productivity-driven methods of modern agriculture are not sustainable in the longer term; the sensitive balance of natural ecosystems is only productive as a whole. There is a shift to return to more sustainable land use, in part as awareness of environmental responsibility increases, but also as it becomes apparent that insensitive use of ecosystems creates alternative problems; decline in soil quality, erosion, flooding and disease to name a few. The management of Laurieston Forest shows a primarily commercial productive forestry industry considering how to adapt its methodology to work with nature more benevolently. Within the plans, there are clear objectives to restore or create areas for species which have been affected by habitat loss.

Changes to forestry techniques, such as those proposed for Laurieston, through reduced clear felling and increased continuous cover forestry (CCF) favour more sustainable harvesting methods which allow for individual trees to be felled, consequently producing mixed age stands with a variety of tree species at different heights and sizes which should ultimately be able to regenerate naturally from self-seeding. This variation allows for the forest floor to retain a healthier ecosystem with improved soil quality and more biodiversity. This kind of close to nature forestry has obvious increased benefit to wildlife, offering a more ‘natural’ habitat than much typical uniform forestry, as well as providing a solution to the impacts of climate change and disease resilience which such monoculture struggles to withstand.

Changes to forestry techniques, through reduced clear felling and increased continuous cover forestry (CCF) favour more sustainable harvesting methods which allow for individual trees to be felled, consequently producing mixed age stands with a variety of tree species at different heights and sizes which should ultimately be able to regenerate naturally from self-seeding. This variation allows for the forest floor to retain a healthier ecosystem with improved soil quality and more biodiversity. This kind of close to nature forestry has obvious increased benefit to wildlife, offering a more ‘natural’ habitat than much typical uniform forestry, as well as providing a solution to the impacts of climate change and disease resilience which such monoculture struggles to withstand.

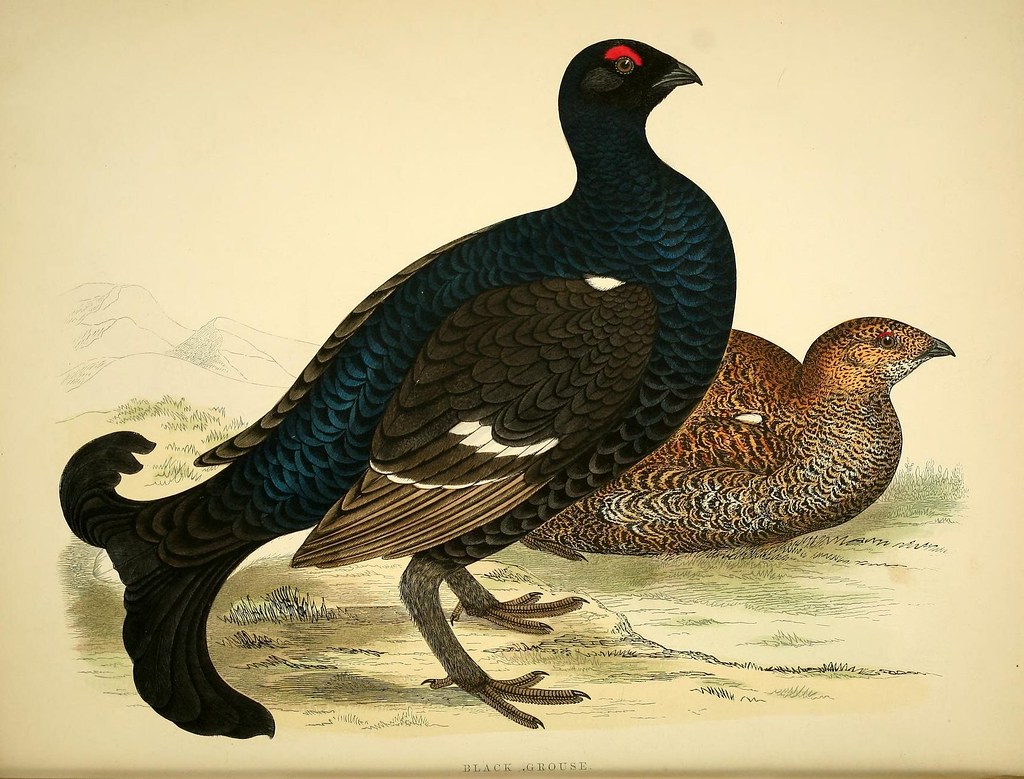

Habitat is also being managed for Black Grouse BAP (Tetrao tetrix) and red squirrel populations.

"n210_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

"n210_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) plate from Coloured figures of the birds of the British Islands / issued by Lord Lilford.. London :R. H. Porter,1885-1897.. litho / colour by E. Neale & J Smith, printed by Mintern bros.

"n41_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

"n41_w1150" by BioDivLibrary is licensed under CC PDM 1.0

Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) plate from British game birds and wildfowl /. London :Groombridge and Sons …,1855..

The plan also includes some deforestation in order to increase areas of open space, particularly around riparian zones, boggy areas and viewpoints. This aims to benefit bird species and increase water quality and allow for some filling in with broadleaf species . An area of open habitat is intended to be created between Loch Whinyeon and Kennick burn. Removal of non-native species in Plantations on Ancient Woodland Sites (PAWS) will aim to restore native woodland through colonisation of surrounding broadleaves. Permanent native broadleaf corridors will also be targeted and increased for biodiversity along the riparian zones of Fuffock Burn, Kennick Burn, Woodhall Loch, Lochenbrek Loch and Loch Whinyeon.

It is great to see Forestry initiatives such as these begin to take responsibility for how they have affected the environment, and collaborate with other parties to look for the best methods to do so. Other ambitious projects to replace plantations and restore treeline woodland and montane scrub extend across the Galloway Forest Park. [17]

Starting with the identification and protection of nature reserves, ancient woodland, plantations and specific trees; careful planning can move on to the clearing and conservation of priority habitats which have been planted on or encroached upon, restoration of riparian zones with native broadleaf species and creation of corridors of mixed planting as well as open spaces. Commercial forests with more natural age and diversity variation should promote a more sympathetic relationship with nature and it is encouraging to see these methods already in practice. For now, the nightjar has moved from the red list to amber [18] (BoCC4, Eaton et al. 2015), and though still depleted, population is increasing [19] (SPEC 3 BirdLife International 2017), evidence of how this kind of unified management can slow or reverse population decline. We can hope that the many less known or recorded species of flora and fauna will also have opportunity to recover.

[1] Annex 1 species, Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32009L0147

also, Appendix II – STRICTLY PROTECTED FAUNA SPECIES https://rm.coe.int/168078e2ff ETS/STE 104 – Bern Convention / Convention de Berne (Appendix/Annexe II), 19.IX.1979 Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats.

[2] Laurieston land management plan https://forestryandland.gov.scot/images/corporate/design-plans/galloway/laurieston/laurieston-land-management-plan.pdf also Laurieston land management plan consultation https://forestryandland.gov.scot/what-we-do/planning/consultations/laurieston

[3] RSPB recording of Nightjar, Niels Krabbe, Xeno-canto https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/wildlife-guides/bird-a-z/nightjar/

[4] Richard D. Gregory, Nicholas I.Wilkinson, David G. Noble, James A. Robinson, Andrew F. Brown, Julian Hughes, Deborah Procter, David W. Gibbons and Colin A. Galbraith. The population status of birds in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man: an analysis of conservation concern 2002-2007. © British Birds 95 • September 2002 • 410-448 http://bailey.persona-pi.com/Public-Inquiries/M4%20-%20Revised/11.3.39.pdf

(abbreviated summary / or link to black grouse info http://www.blackgrouse.info/Birds%20of%20conservation%20concern%202002-2007.pdf )

(RSPB abbreviated summary https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/conservation-science/state-of-the-uks-birds_2002.pdf

Gregory RD, Eaton MA, Noble DG, Robinson JA, Parsons M, Baker H, Austin G and Hilton GM (2003). The state of the UK’s birds 2002. The RSPB, BTO, WWT and JNCC, Sandy.)

[5] UK Biodiversity Action Plan, (Joint Nature Conservation Committee) BAP, Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework – https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap/

UK BAP priority species and habitats – https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/uk-bap-priority-species/

UK Post-2010 Biodiversity Framework – http://data.jncc.gov.uk/data/587024ff-864f-4d1d-a669-f38cb448abdc/UK-Post2010-Biodiversity-Framework-2012.pdf

The Scottish Biodiversity Strategy – https://www.nature.scot/scotlands-biodiversity/scottish-biodiversity-strategy

Document 1 – https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-biodiversity—its-in-your-hands/

Aichi Biodiversity Targets – https://www.cbd.int/sp/targets/

[6] A. Morris , D. Burges , R. J. Fuller , A. D. Evans & K. W. Smith (1994). The status and distribution of Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus in Britain in 1992. A report to the British Trust for Ornithology, Bird Study, 41:3, 181-191, DOI: 10.1080/00063659409477218 https://doi.org/10.1080/00063659409477218

[7] Conway, G. & Henderson, I., 2005. The Status and Distribution of The European Nightjar Caprimulgus Europaeus in Britain in 2004 © British Trust for Ornithology. 2004 report by BTO data. ISBN: 978-1-906204-43-3 https://www.bto.org/sites/default/files/shared_documents/publications/research-reports/2005/rr398.pdf

[8] Greg Conway, Simon Wotton, Ian Henderson, Rowena Langston, Allan Drewitt & Fred Currie (2007) Status and distribution of European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus in the UK in 2004, Bird Study, 54:1, 98-111, DOI: 10.1080/00063650709461461 https://doi.org/10.1080/00063650709461461

[9] RSPB press release, 5th October 2016. One of Scotland’s rarest birds thriving in Dumfries and Galloway, Jenny Tweedie – https://www.rspb.org.uk/about-the-rspb/about-us/media-centre/press-releases/one-of-scotlands-rarest-birds-thriving-in-dumfries-and-galloway/

FES blog 19th October 2016. Modern forestry benefits the nightjar – https://forestryandland.gov.scot/blog/modern-forestry-benefits-the-nightjar

[10] Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (2017). Nightjar breeding season surveys in Dumfries and Galloway between 1981 and 2011. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/d3oo4b accessed via GBIF.org on 2020-09-11.

[11] Alexander, I and Cresswell, B. (1990), Foraging by Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus away from their nesting areas. Ibis, 132: 568-574. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1990.tb00280.x https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1990.tb00280.x

[12] Sharps, K., Henderson, I., Conway, G., Armour‐Chelu, N. and Dolman, P.M. (2015), Home‐range size and habitat use of European Nightjars Caprimulgus europaeus nesting in a complex plantation‐forest landscape. Ibis, 157: 260-272. doi:10.1111/ibi.12251 https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12251

see also linked articles:

[13] Coloured figures of the birds of the British Islands, issued by Lord Lilford, F.Z.S, president of the British Ornithologists’ Union. Vol 2. 1885-1897.

Citation from document availiable at Biodiversity Heritage Library – https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/34524440#page/71/mode/1up

Image also available at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/82/Caprimulgus_europaeus_-Coloured_figures_of_the_birds_of_the_British_Islands_%281885-1897%29.jpg

Creative commons image page – https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/ff262a1d-e888-47ef-8af6-af9726131b01

[14] Page, C. (1982). The history and spread of bracken in Britain. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Section B. Biological Sciences, 81(1-2), 3-10. doi:10.1017/S0269727000003201 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-royal-society-of-edinburgh-section-b-biological-sciences/article/history-and-spread-of-bracken-in-britain/8F42E36E6E6E5BB88448CB20CB6A1274

[15] Stewart, G.B., Tyler, C. & Pullin, A.S. 2005. Effectiveness of current methods for the control of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum). CEE protocol 04-001 (SR3). Collaboration for Environmental Evidence: www.environmentalevidence.org/SR3.html.

[16] A guide to understanding the Scottish Ancient Woodland Inventory (AWI), Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH) (now NatureScot) https://www.nature.scot/guide-understanding-scottish-ancient-woodland-inventory-awi

[17] Soutar, R. Mountain woodland in the Galloway Forest Park Scrubbers’ Bulletin No. 9, Montane Scrub Action Group, December 2011, pages 4-9. http://www.mountainwoodlands.org/userfiles/file/Publications/Scrubbers_Bulletin_9.pdf

see also https://forestryandland.gov.scot/blog/new-native-woodland-in-galloway?highlight=All

[18] Eaton M.A, Aebischer N.J, Brown A.F, Hearn R.D, Lock L, Musgrove A.J, Noble D.G, Stroud D.A and Gregory R.D (2015) Birds of Conservation Concern 4: the population status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man © British Birds 108, 708–746.https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/documents/conservation-projects/bocc4-report.pdf

see also summarised report from BTO – https://www.bto.org/sites/default/files/shared_documents/publications/birds-conservation-concern/birds-of-conservation-concern-4-leaflet.pdf

[19] BirdLife International (2017) European birds of conservation concern: populations, trends and national responsibilities Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International. ISBN 978-1-912086-00-9 https://www.birdlife.org/sites/default/files/attachments/European%20Birds%20of%20Conservation%20Concern_Low.pdf